Gambling with Faith

Pascal's Wager: Faith over Reason, a Religious or Philosophical Position

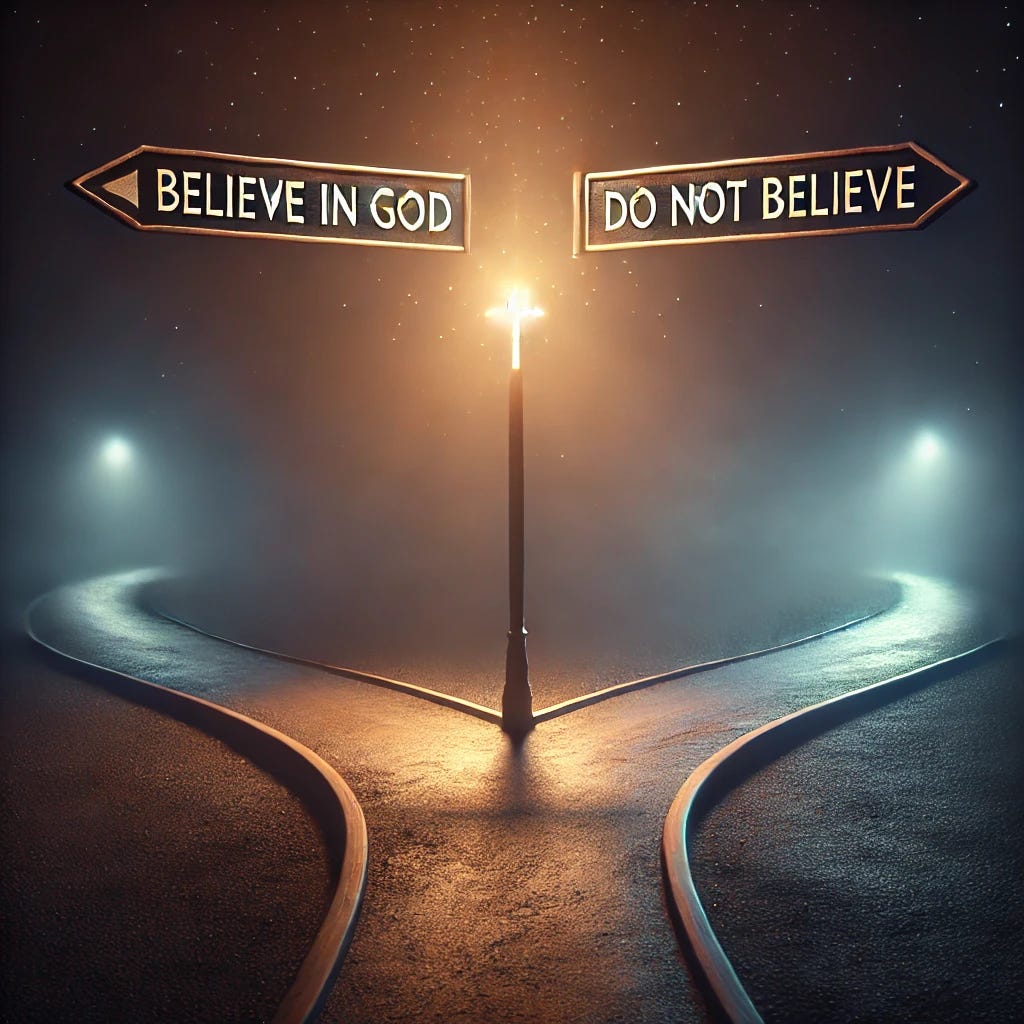

“It is in one's best interest to believe in God, even if the existence of God cannot be proven.” Or is it? Blaise Pascal, a seventeenth-century French philosopher and mathematician, argued that if you believe in God and He exists, you stand to gain eternal happiness. Conversely, if you don’t believe and God does exist, you risk eternal damnation. If God doesn’t exist, the believer loses nothing of ultimate value. Thus, wagering on God’s existence is presented as the most rational choice because the potential benefits far outweigh the potential losses. This argument is famously known as Pascal’s Wager.

"God is, or He is not. But to which side shall we incline? Reason can decide nothing here. There is an infinite chaos which separates us. A game is being played at the extremity of this infinite distance where heads or tails will turn up... Which will you choose then? Let us see. Since you must choose, let us see which interests you least. You have two things to lose: the true and the good; and two things to stake: your reason and your will, your knowledge and your happiness; and your nature has two things to avoid: error and misery. Your reason is no more shocked in choosing one rather than the other, since you must of necessity choose. This is one point settled. But your happiness? Let us weigh the gain and the loss in wagering that God is. Let us estimate these two chances. If you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing." (Pensées 233)

Despite its initial appeal, Pascal’s Wager oversimplifies the complexities of belief by assuming only two options: belief in the Christian God or non-belief. Often cited by Christians when engaging with skeptics, the Wager is presented as a rational choice with potentially infinite rewards and minimal risks. However, in reality, the religious landscape is far more diverse, with countless faiths, each making its own claims about divinity and the afterlife. This plurality makes the Wager less compelling, as it overlooks the possibility that other religious systems offer their own promises of salvation or consequences for disbelief. When considered in the broader context of world religions, Pascal's Wager loses much of its force.

Faith in an Age of Uncertainty

Pascal lived during a time of significant religious and philosophical upheaval. The Protestant Reformation, which had begun more than a century earlier, had fractured the Catholic Church, sparking intense debates over faith, salvation, and authority. Meanwhile, the Scientific Revolution was gaining momentum, with thinkers like Galileo and Descartes challenging traditional views about the natural world. As a devout Catholic, Pascal was deeply influenced by these intellectual shifts. His work Pensées was not just an abstract philosophical exercise but a response to the growing skepticism of his time. Recognising that reason alone could neither prove nor disprove God’s existence, Pascal turned to a pragmatic approach, best encapsulated in his famous Wager.

The Pensées was intended as a comprehensive defence of Christianity, and Pascal’s Wager was a key component of this effort. Influenced by his background in mathematics, probability, and decision theory, Pascal framed belief in God as a gamble with potentially infinite rewards. Given the limitations of human reason, he argued, it was rational to “wager” on God’s existence, since the potential benefits of eternal happiness far outweighed the risks of disbelief. This cost-benefit analysis was Pascal’s way of addressing the intellectual climate of religious and philosophical uncertainty.

Ethics and the Limits of Pascal's Wager

Modern philosophers have raised objections to Pascal’s Wager, particularly in light of contemporary ethical and epistemological standards. One notable critique comes from philosopher John Schellenberg, who introduced the concept of “non-resistant non-believers.” Schellenberg argues that many people, despite sincerely searching for God, may never find sufficient evidence to justify belief. Pascal’s Wager assumes that belief is a simple, conscious choice, but Schellenberg’s critique highlights that for many, belief remains elusive despite earnest searching. This raises a moral question: should individuals be punished for failing to believe in something for which they find no compelling evidence?

Pascal’s Wager also doesn’t address the issue of whether it’s ethical to believe in something just to avoid punishment. From a modern standpoint, such pragmatism feels hollow, as it suggests that fear of damnation should override the pursuit of truth or personal integrity. Philosophers like Bertrand Russell and Richard Dawkins have critiqued belief systems grounded in fear, labelling them intellectually dishonest. It may be more important, they argue, to live authentically rather than hedging one’s bets out of fear of potential punishment.

The Oversight of Religious Pluralism

Pascal’s Wager assumes a false dichotomy - Christianity versus non-belief - ignoring the possibility that other gods or religious systems might be true. This oversight is particularly problematic given the vast plurality of religious beliefs worldwide. Many faiths, like Islam, promise eternal paradise for believers and punishment for non-believers, while others, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, offer different paths to spiritual fulfilment or reincarnation based on one's actions. This reveals that the argument could theoretically apply to any religion offering similar rewards or punishments, complicating the decision. If the wager can be applied to any deity or belief system, the choice is no longer a simple binary between belief and disbelief, instead a complex question of which god or religion to follow. This diversity of religious perspectives weakens the force of Pascal’s argument, as it fails to account for the many alternatives to Christian belief.

The Wager assumes that belief is a simple, risk-free choice, when in reality, genuine belief cannot be reduced to a pragmatic decision. True belief involves deep personal conviction. William James, in The Will to Believe, argues that belief should be grounded in sincere faith, not mere calculation. Living according to a belief one doesn’t truly hold risks compromising personal integrity and authenticity.

Risk Aversion

Psychologically, Pascal’s Wager taps into a fundamental human tendency: risk aversion. Studies in behavioural economics, particularly by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in the 1970s, demonstrate that people tend to avoid risks with potentially severe outcomes, even when the probability is low. Kahneman and Tversky, known for developing Prospect Theory, showed that people are more sensitive to potential losses than to equivalent gains - a concept known as loss aversion. This may explain why Pascal’s Wager appeals to so many, as it offers a psychological safety net for those fearing the unknown after death. Yet, forming beliefs should not be driven solely by risk aversion but by genuine conviction and evidence. Fear of eternal damnation may be a powerful motivator, but it is not a justifiable reason to adopt beliefs one does not truly hold.

The Broader Implications of Pascal’s Wager

If we apply Pascal’s logic to other areas of life, its shortcomings become clearer. Imagine choosing a career or life partner based solely on the least negative outcome. This approach might minimise risk, but it denies the possibility of pursuing genuine passion or love. Similarly, Pascal’s Wager suggests that belief in God should be motivated by a fear of punishment rather than sincere conviction. Such decision-making undermines the pursuit of truth and personal fulfilment, encouraging a life led by fear rather than a commitment to authenticity.

Imagine being given a key to a hotel room, told that inside lies eternal treasure, but warned that choosing the wrong room (or no room at all) risks eternal loss. With countless rooms (representing various religions) and no clear indication which is correct, would it be rational to randomly select a room solely to avoid potential loss? This scenario highlights Pascal's Wager's failure to account for the vast array of religious options and the lack of empirical evidence to guide decision-making.

The “What If You’re Wrong?” Question

A common challenge posed by Christians is, “What if you’re wrong?” This question aims to make non-believers consider the potential consequences of disbelief. However, it is equally valid to ask Christians, “What if you are wrong?” If non-believers are expected to wager on Christianity, believers should also consider the possibility that their own belief might be incorrect. For instance, imagine arriving at the Pearly Gates, only to be met by Ahura Mazda (Zoroastrian Deity), who condemns you for not believing in him and instead following the Christian God. You’ve chosen the wrong god and now face eternal consequences. Such a scenario hardly seems just, especially given the lack of empirical evidence for either Ahura Mazda or the Christian God. A truly moral and just god would not punish someone for withholding belief in the absence of sufficient evidence. In light of this, wouldn’t it be more reasonable to withhold belief in any particular deity, rather than risk eternal punishment for choosing incorrectly? The world is home to a diverse array of religions, many of which claim exclusivity, complicating Pascal’s simplistic binary of belief versus disbelief.

Reassessing Pascal’s Wager

Pascal’s Wager offers an intriguing argument for belief in God, but it is fundamentally flawed. It oversimplifies the complexity of religious belief, ignores the diversity of world religions, and undervalues the role of evidence and sincere conviction. In today’s context, faith demands more than a pragmatic gamble; it requires thoughtful consideration of both ethical and evidential dimensions. Instead of relying on fear-driven calculations, we should prioritize critical thinking, empathy, and genuine inquiry. Recognizing the limits of Pascal’s Wager opens the door to more meaningful discussions about faith, morality, and what it means to live authentically.

Sources:

Pascal, Blaise. Pensées. Translated by A.J. Krailsheimer, Penguin Classics, 1995.

Schellenberg, John L. The Wisdom to Doubt: A Justification of Religious Skepticism. Cornell University Press, 2007.

James, William. The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy. Dover Publications, 1956.

Russell, Bertrand. Why I Am Not a Christian: And Other Essays on Religion and Related Subjects. Simon & Schuster, 1957.

Dawkins, Richard. The God Delusion. Mariner Books, 2006.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. Existentialism is a Humanism. Yale University Press, 2007.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Gay Science. Translated by Walter Kaufmann, Vintage Books, 1974.

Hick, John. God Has Many Names. Westminster John Knox Press, 1982.

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011.