Genesis: The Patriarch Effect

Favouritism, Moral Ambiguities, Misogyny and Possible Plagiarism

As I continued to quench my thirst for knowledge, I delved deeper into the patriarchal plots of the Bible, particularly in the Book of Genesis. These stories, which have long been revered as foundational accounts of the origins of the Israelite nation, center around figures like Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph. They are often celebrated for their depiction of faith, divine promises, and the establishment of an agreement between God and His chosen people. However, a closer examination reveals deep ethical and moral issues within these narratives. They expose troubling aspects of the patriarchal system, including misogyny, moral ambiguities, and the potential harm these passages have perpetuated through their interpretation and application over centuries.

One of the most unsettling stories in the Abrahamic narrative is the binding of Isaac (Genesis 22), where God commands Abraham to sacrifice his son. This story is often cited as the ultimate test of faith and obedience to God. However, the ethical implications of this narrative are profound. Abraham’s willingness to kill his son raises serious questions about the morality of blind obedience to divine commands. The story implicitly endorses the idea that unquestioning faith and obedience are virtues, even when they lead to actions that are morally reprehensible by modern standards.

This narrative reflects the broader patriarchal system that values male authority and power above all else. Isaac’s near sacrifice illustrates how the lives of individuals, particularly children, are subjected to the impulses of male-controlled figures. The moral lesson derived from this story is deeply troubling: it suggests that the ends justify the means and that loyalty to authority, even divine authority, can override basic human ethics.

The story of Jacob and Esau is another narrative laden with ethical dilemmas. Jacob, with the help of his mother Rebekah, deceives his father Isaac to steal the blessing meant for Esau, his elder brother (Genesis 27). This act of deception is rewarded, with Jacob becoming the father of the twelve tribes of Israel. The narrative glorifies cunning and manipulation, raising questions about the moral lessons it imparts.

The favouritism presented by the patriarchs, whether it’s Isaac favouring Esau or Jacob favouring Joseph, also preserves divisions and conflicts within families. These stories suggest that favouritism and deceit are acceptable means to achieve divine favour, a notion that is ethically problematic and potentially harmful when applied to real-life situations.

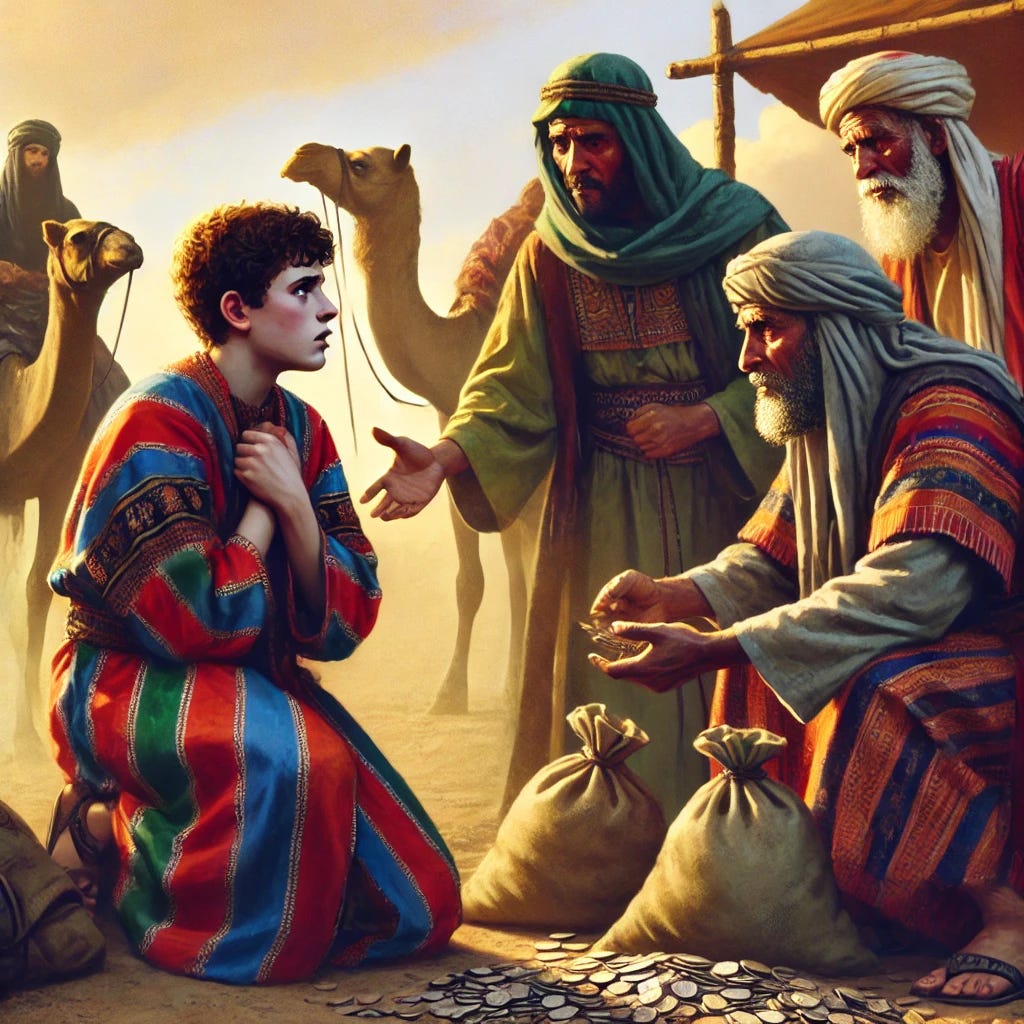

Joseph’s story, often portrayed as a tale of redemption and divine providence, also raises significant moral concerns. His brothers conspire to rid themselves of him, ultimately selling him into slavery. Joseph’s rise to power in Egypt, following this betrayal and enslavement, is marked by divine favour. However, this narrative implicitly condones the idea that suffering and exploitation can be justified as long as they lead to a greater good. While Joseph’s eventual forgiveness of his brothers is often seen as noble, it also glosses over the trauma and injustice he endured.

This account preserves the notion that divine favour is linked to material success and power, reinforcing the belief that wealth and authority are signs of righteousness. This message is problematic, as it equates moral worth with social and economic status, thereby justifying inequality and the abuse of power.

It also raises troubling questions about the portrayal of God, who appears to condone or even orchestrate the events leading to Joseph's suffering. Despite the cruelty of Joseph’s treatment, the story suggests that his eventual rise to power in Egypt is part of a divine plan, implying a God who permits harm and suffering as a means to achieve a greater purpose. This depiction challenges traditional notions of divine justice and benevolence, and forced me to confront the unsettling idea of a God seemingly more invested in power struggles than in the immediate well-being of individuals.

Ultimately, the betrayal of Joseph serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unquestioning faith, the toxic effects of dysfunctional family dynamics, and the portrayal of a deity whose actions may provoke more questions than comfort in the pursuit of moral and ethical understanding. The story stresses the patriarchal nature of the society in which these events unfold, where the experiences of women like Dinah and Tamar are marginalized, reduced to mere footnotes in a broader tale dominated by male protagonists. Their stories, often overshadowed by the struggles and triumphs of men, reflect a societal structure that values male power and authority above the lives and dignity of women.

Females in these stories are often treated as property or bargaining chips, their worth measured by their ability to produce heirs. For instance, Sarah, Abraham’s wife, is twice handed over to foreign rulers by Abraham to protect himself (Genesis 12:10-20, 20:1-18). This act not only reflects the commodification of women but also raises ethical questions about Abraham’s character as a patriarch and a moral leader.

Hagar, Sarah’s Egyptian servant, is another tragic figure in these accounts. After Sarah’s initial inability to conceive, she offers Hagar to Abraham to produce an heir (Genesis 16). Hagar’s subsequent mistreatment and eventual banishment, along with her son Ishmael, expose the cruelty and exploitation inherent in the patriarchal system. The story of Hagar reflects the broader societal norms that devalue and dehumanize women, especially those of lower status or foreign origin. Ultimately revealing significant misogyny and the subjugation of woman.

Similarly, the stories of Leah and Rachel, the two wives of Jacob, further highlight the patriarchal control over women’s lives. Both women are essentially traded between men - first by their father Laban and then by Jacob - based on their ability to bear children. Leah, who is less favoured by Jacob, endures a life of neglect and sorrow, while Rachel, the preferred wife, also suffers under the pressures of producing male heirs. These stories illustrate the deep-seated chauvinism within the patriarchal framework, where women’s value is reduced to their reproductive capabilities and their role as vessels for male lineage.

I find that the patriarchal stories in the Bible, while foundational to the religious traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, present profound ethical and moral challenges. These narratives uphold male dominance, condone the subjugation of women, and justify deception and favouritism. The continued awe of these stories without critical examination prolongs patriarchal values that are incompatible with modern ethics and human rights. It is crucial to scrutinize these narratives, not only to understand their historical and cultural context but also to challenge the harmful ideologies they spread. By doing so, we can begin to dismantle the patriarchal structures long supported by these ancient texts and move toward a more unbiassed and just society.

Another interesting point I recently uncovered is the hypothesis that the Pentateuch may have been influenced by or even copied from Plato’s work. While speculative, it raises intriguing questions about the origins and development of these seminal texts. This comparison accentuates the deep interconnection between philosophical and theological thought in the ancient world, where cultural and intellectual exchanges were more fluid than we often assume. Plato's exploration of ideal realities, moral order, and the nature of justice shares surprising parallels with the themes found in the Pentateuch, such as the concept of divine law, ethical living, and the establishment of a just society.

The timing of these texts' final compositions, particularly during periods of significant cultural interaction, lends some weight to the hypothesis. For example, the final form of the Pentateuch is believed to have been solidified during or after the Babylonian exile, a period when the Israelites were exposed to various cultural influences, including those from Greek thought. Meanwhile, Plato’s works were being developed in a vibrant intellectual environment in Greece, with ideas that could have traveled and been absorbed into other traditions.

Critically examining these potential influences is vital, as it helps to uncover the layers of thought and tradition that have shaped religious texts over time. This not only deepens our understanding of the Pentateuch but also challenges us to reconsider the rigid boundaries we often place between philosophy and theology. By exploring the possible cross-pollination of ideas, we gain a more nuanced view of how religious and philosophical concepts have evolved, highlighting the interconnectedness of human thought across different cultures and eras.

Sources:

“The Bible As It Was” J.L. Kugel. Havard University Press. 1997

“The Hebrew Goddess” R. Patai. Wayne State University Press. 1959

“The Torah: A Modern Commentary” W.G. Plaut. Union for Reform Judaism. 1981

“The Republics and Phaedrus” Plato. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

“A History of God: The 4,000-Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam” K. Armstrong. Ballantine Books 1993.

“Abraham in History and Tradition” John Van Seter. Yale University Press, 1975.

“Who Wrote the Bible?” Richard E. Friedman. HarperOne, 1997

“Leviticus 1-16: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary” Jacob Milgrom. Anchor Bible Series, 1991

“The Art of Biblical Narrative” Robert Alter. Basic Books, 1981

“History of the Conflict Between Religion and Science” John W Draper 1984