God in Your Bones?

When Pattern-Hunting Masquerades as Proof

Every now and then, a piece of Christian content circulates online that feels profound, intimate, and quietly overwhelming. It speaks of hidden design, divine fingerprints, and secret meanings etched into the human body itself. In one such posts, which came up on my feed recently, claimed that God ‘carved Himself into you’, pointing to anatomy, neuroscience, and numerology as evidence that Christianity is literally written into our bones.

At first glance, it sounds poetic. Look a bit closer, and the poetry is doing all the work — and none of it withstands scrutiny.

This is not theology in any serious sense, nor is it science. It is something far more familiar and far older: humans finding patterns, assigning meaning, and mistaking psychological salience for revelation.

Sacred Numbers and an Ancient Habit

The post leans heavily on numbers. Thirty-three. Twelve. Three. To a modern reader, these feel unmistakably Christian. Historically, they are anything but.

Long before Christianity existed, cultures across the ancient world treated certain numbers as symbolically significant. Twelve appears in Babylonian astrology with the zodiac signs, in Egyptian cosmology, and later in Greek religious and philosophical systems. Three shows up everywhere: the Hindu Trimurti of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva; Norse mythological narratives that frequently organise figures and events in threes; and Celtic traditions that emphasised triple deities. These numbers recur not because they encode divine truth, but because humans gravitate towards them cognitively and culturally. They feel complete, balanced, and meaningful, even when they are arbitrary.

Christianity did not invent sacred numbers; it inherited and repurposed them. When believers later discover these same numbers in anatomy, history, or nature, it feels revelatory only because the conclusion is already in place.

Thirty-Three Vertebrae and a Convenient Tradition

The claim that Jesus died at thirty-three years old is not found anywhere in the Gospels. It is a later tradition, repeated until it feels historical. The idea that the human spine conveniently contains thirty-three vertebrae fares no better. Humans do not consistently have this number. Some have fewer, some more, and several vertebrae naturally fuse together during development. In functional terms, most adults do not even experience their spines as ‘thirty-three units’.

If Jesus were believed to have died at thirty-four, or thirty, or forty, this comparison would never have arisen. The anatomy is constant; the symbolism is flexible. That alone should tell us which part is driving the interpretation.

Twelve Ribs, Twelve Disciples, and the Illusion of Design

Humans have twelve pairs of ribs because that is how mammals evolved. Many animals share the same structure. The fact that Israel had twelve tribes and Jesus later chose twelve disciples says nothing about divine engineering. It says something about cultural continuity and symbolic inheritance.

If rib counts were evidence of God’s covenant, then dogs, whales, and chimpanzees are inexplicably included. The more plausible explanation is the simplest one: theology is being projected onto biology, not discovered within it.

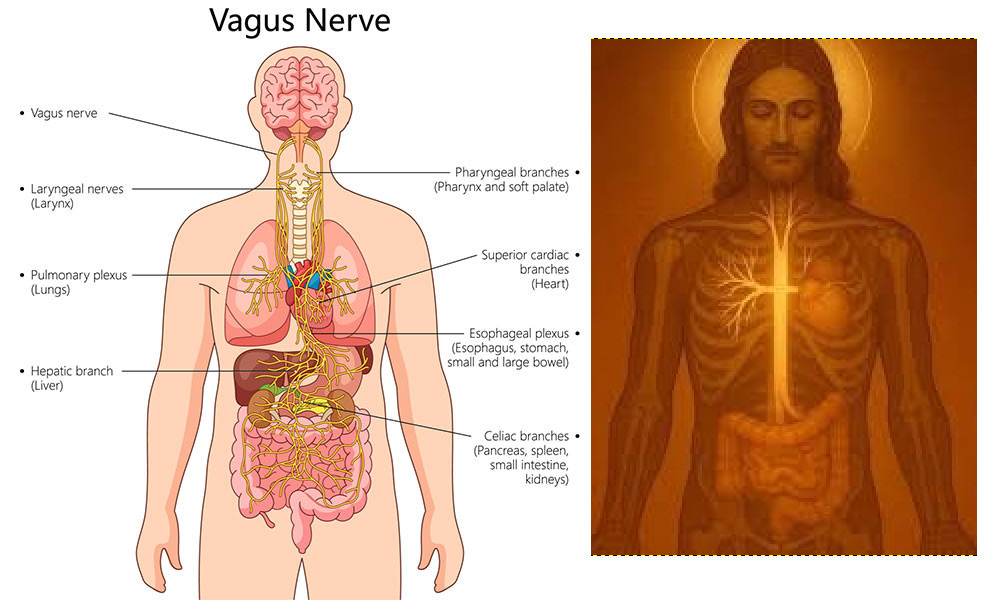

The Vagus Nerve and Projected Symbolism

The vagus nerve does not resemble a cross. Anatomically, it is branching and tree-like, spreading through the chest and abdomen. The cross comparison exists only because Christians already regard the cross as sacred. It is more like projection, and not perception.

Its function is well understood: regulation of the parasympathetic nervous system, calming the body during stress. That prayer can activate this response is unsurprising. Meditation, breathing exercises, and even music do the same. Other religions have long found their own sacred meanings in the body: chakras in Hinduism, meridians in traditional Chinese medicine. Each tradition ‘discovers’ its own symbols in anatomy. The body has not changed. The stories imposed upon it have changed.

Fasting, Autophagy, and the Misuse of Science

Autophagy is not a resurrection mechanism, nor does it begin neatly on the third day of fasting. It is a continuous cellular process that varies depending on numerous factors. The popular claim that ‘three days equals regeneration’ is simplified wellness rhetoric, not rigorous biology.

Fasting is practised across religions: Ramadan in Islam, Yom Kippur in Judaism, ascetic traditions in Buddhism. If fasting proves divine design, then it proves all of them at once — which is to say, it proves none of them.

Tears, Electricity, and Non Sequitur Wonder

Emotional tears differ chemically from irritant tears. This reflects complex biology, not supernatural authorship. The heart’s electrical rhythm and the brain’s activity during prayer are measurable because they are physical systems. To leap from complexity to divinity is a non sequitur. Wonder does not automatically imply intention, and intention does not imply a particular god.

The post also claimed that ‘the blood speaks’ and that ‘bones store memory’. The first is biblical metaphor (Genesis 4:10), not physiology. The second conflates cutting-edge research on epigenetics and cellular memory with something mystical and intentional. Yes, bones contain stem cells and immune memory, but this isn’t devine language, we call it biochemistry. Poetic framing cannot transform material processes into spiritual truths.

Why We Fall for This

Taken individually, each claim is either misleading or outright false. Taken together, they form a familiar apologetic tactic: stacking weak arguments to manufacture the feeling of overwhelming confirmation. This is not how truth is discovered. It is how pattern-hunting is dressed up as evidence.

What is happening here has names. Apophenia is the human tendency to see meaningful connections between unrelated things. Confirmation bias filters information so that only supporting data is noticed. The Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy draws the target around where the bullets already landed.

This is apologetics by accumulation. No single claim needs to stand, because the emotional weight comes from their sheer number.

These same cognitive habits produce conspiracy theories, fortune-telling, and pareidolia — faces in clouds, messages in noise. Religion does not escape these mechanisms; it exploits them.

Why This Rhetoric Works

Posts like this resonate because they offer certainty in an uncertain world. They make an abstract God tangible: your spine, your breath, your heartbeat. They bypass critical scrutiny by anchoring belief in bodily experience. And they create intimacy — the comforting idea that the creator of the universe has left personalised signatures inside you.

The closing line, ‘You don’t need to look far’, quietly discourages external verification. If truth is found inwardly, evidence becomes unnecessary. Disagreement becomes a failure to feel, not a reason to question.

The Danger of Looking Only Inward

This framing renders faith unfalsifiable. If you feel God, He is real. If you do not, you are not looking hard enough. Truth becomes private, immune to challenge, and impossible to distinguish from delusion.

Historically, this logic has justified everything from sincere spiritual experiences to manipulative cult control. When inner conviction replaces shared standards of evidence, there is no principled way to tell revelation from imagination.

Awe Without Illusion

The human body is remarkable. Four billion years of evolution produced systems of extraordinary complexity and resilience. The vagus nerve does not need divine authorship to inspire awe — its real function is more elegant than any metaphor. Naturalistic wonder does not cheapen reality; it honours it.

As Carl Sagan observed, understanding how something works does not make it less beautiful. It makes it more honest. We do not need to see gods in our anatomy to feel reverence for what we are.

What’s at Stake

For many believers, ideas like these feel like a direct line to God. Losing them can feel like losing presence, intimacy, and meaning. The emotional cost of deconstruction is real. But truth-seeking has never promised comfort. It can only promise clarity.

Letting go of comforting narratives is painful, but clinging to them does not make them true and sometimes not easier either.

Conclusion

If God truly carved Himself into us, the evidence would not require such elaborate interpretation, selective science, and symbolic gymnastics. The fact that every religion finds its own theology mirrored in the human body tells us something important — and it is not about divine design.

We can admire the human body without seeing our beliefs reflected back at us. We can feel wonder without inventing worship. We can live with meaning without requiring mythology. And we can seek truth without insulating ourselves from the questions it demands.

Sources:

Armstrong, Karen. A History of God. London: Vintage, 1999.

Barrett, Justin L. Why Would Anyone Believe in God? Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 2004.

Benson, Herbert, and William Proctor. Relaxation Revolution. New York: Scribner, 2010.

Breit, S., A. Kupferberg, G. Rogler, and G. Hasler. “Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain–Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 9 (2018): 44.

Brown, Raymond E. An Introduction to the New Testament. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985.

Coyne, Jerry A. Faith Versus Fact: Why Science and Religion Are Incompatible. London: Viking, 2015.

Dennett, Daniel C. Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. New York: Viking, 2006.

Ehrman, Bart D. Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Frey, William H. Crying: The Mystery of Tears. Minneapolis: Winston Press, 1985.

Gilovich, Thomas. How We Know What Isn’t So: The Fallibility of Human Reason in Everyday Life. New York: Free Press, 1991.

Hopper, Vincent Foster. Medieval Number Symbolism: Its Sources, Meaning, and Influence on Thought and Expression. New York: Dover Publications, 2000.

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Penguin Books, 2011.

Levine, Beth, and Guido Kroemer. “Autophagy in the Pathogenesis of Disease.” Cell 132, no. 1 (2008): 27–42.

Longo, Valter D., and Mark P. Mattson. “Fasting: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Applications.” Cell Metabolism 19, no. 2 (2014): 181–92.

Mizushima, Noboru, and Daniel J. Klionsky. “Protein Turnover Via Autophagy: Implications for Metabolism.” Annual Review of Nutrition 27 (2007): 19–40.

Moore, Keith L., Arthur F. Dalley, and Anne M. R. Agur. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2018.

Porges, Stephen W. The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. New York: W. W. Norton, 2011.

Sagan, Carl. The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. London: Headline Book Publishing, 1997.

Sanders, E. P. The Historical Figure of Jesus. London: Penguin Books, 1996.

Shermer, Michael. The Believing Brain: From Ghosts and Gods to Politics and Conspiracies—How We Construct Beliefs and Reinforce Them as Truths. New York: Times Books, 2011.

Shubin, Neil. Your Inner Fish: A Journey into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body. London: Penguin Books, 2009.

Standring, Susan, ed. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. 41st ed. London: Elsevier, 2016.

Vingerhoets, Ad J. J. M. Why Only Humans Weep: Unravelling the Mysteries of Tears. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.