The Trinity Hoax

Origins, Invention, and the Illusion of Divine Unity

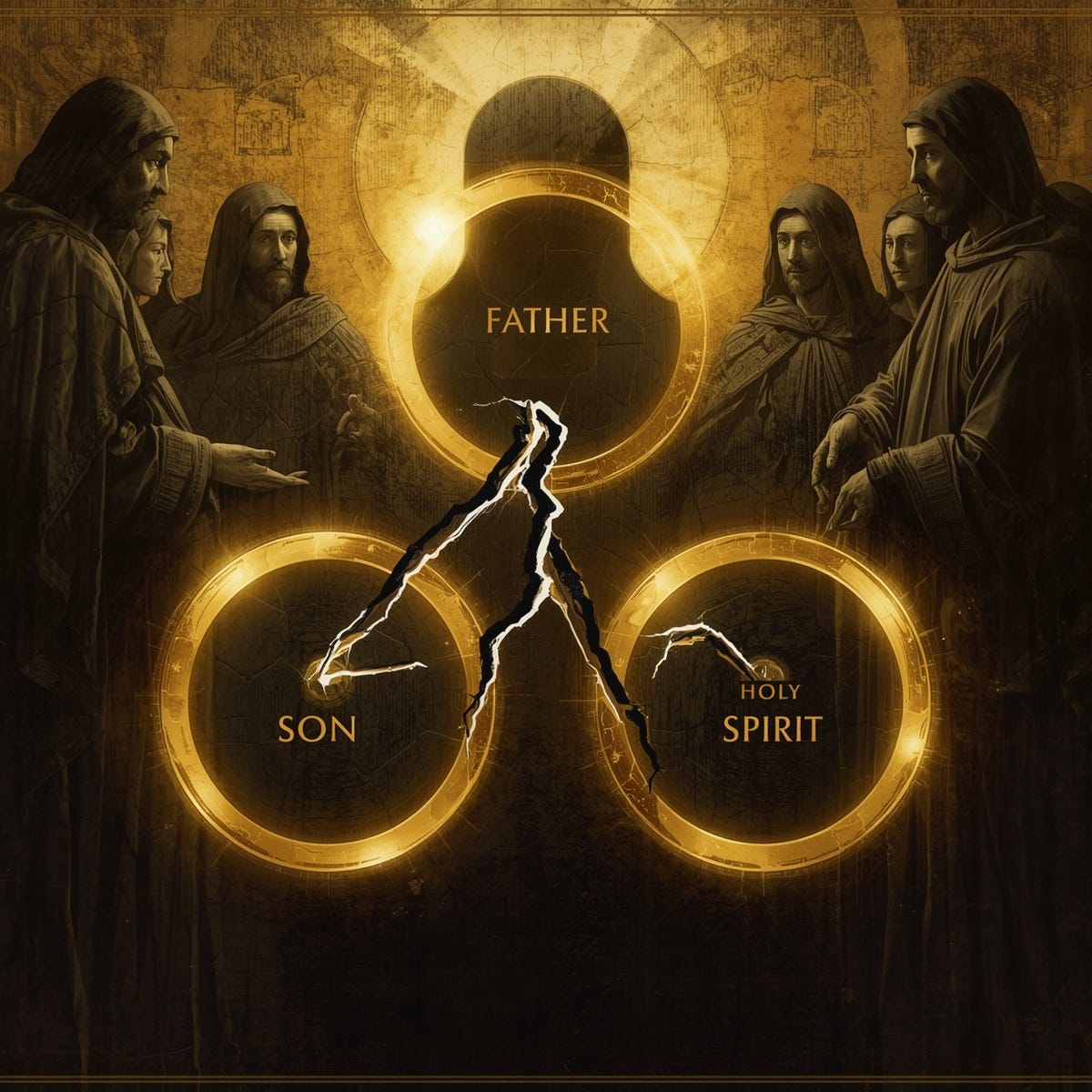

Few doctrines in Christianity are as central — and as confusing — as the Trinity. The claim that God is one being in three persons, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, is considered “orthodox” belief, yet it is also one of the most philosophically incoherent ideas in Christian theology. The Bible itself never once uses the word Trinity, nor does it explicitly spell out the concept. What Christians today take as fundamental was, in reality, a slow, messy invention of church councils, theological compromises, and political manoeuvring.

To understand the Trinity, we need to ask some uncomfortable questions: Where did this idea come from? Why was it accepted? How do Christians interpret it? And ultimately, does it make any sense at all?

The Biblical Starting Point — or Lack Thereof

The first surprise for many is that the Bible never clearly teaches the Trinity. In the Hebrew Scriptures, God is relentlessly one. “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one” (Deuteronomy 6:4). Yahweh is not depicted as three-in-one but as a single, indivisible deity, jealous of rivals (Exodus 20:3–5).

Jesus himself seems to uphold this same monotheism. When asked what the greatest commandment is, he quotes the Shema: “The Lord our God, the Lord is one” (Mark 12:29). He frequently refers to God as his Father, but he never once says, “I am God” or “Worship me as part of a Trinity.”

Instead, we get fragments that later theologians would latch onto. The Gospel of John contains the high Christology many Trinitarians rely on: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1:1). Likewise, Jesus says, “I and the Father are one” (John 10:30). Yet later on in John, Jesus makes his subordination clear: “The Father is greater than I” (John 14:28).

As for the Holy Spirit, the Old Testament usually treats “spirit” as the breath, presence, or power of God, not a distinct person. In the New Testament, the Spirit plays an active role but is still ambiguous. Is it God’s empowering presence, or a separate entity? The text never resolves the question.

In short, the so-called “evidence” for the Trinity in Scripture is contradictory at best. If the Trinity were truly the centre of God’s revelation, one might reasonably expect the Bible to state it clearly. It never does.

The Birth of a Doctrine

If the Trinity is not explicitly biblical, where did it come from? The answer lies in the early centuries of Christianity, as leaders tried to reconcile competing ideas about Jesus and God.

Early Christians were divided. Some believed Jesus was fully divine. Others argued he was created by God and therefore subordinate. Still others thought of him as a human uniquely empowered by God’s spirit. This diversity created conflict — especially as Christianity spread through the Roman Empire.

Enter the councils

The Council of Nicaea (325 CE), convened by Emperor Constantine, was less about divine truth and more about unity in the empire. Arianism, which taught that the Son was created and therefore not eternal, had become a popular alternative. The bishops at Nicaea rejected this view, declaring that Jesus was “of one substance” (homoousios) with the Father.

But even then, the Spirit was still undefined. It wasn’t until the Council of Constantinople (381 CE) that the Spirit was elevated to full divine status, completing the “three persons in one essence” formula.

Thus, the Trinity was not discovered in Scripture but hammered out in debate halls, shaped by politics as much as theology. It was codified in creeds not because it was obvious, but because the Church needed a unified doctrine to silence dissent.

Philosophical Gymnastics and Theological Confusion

Christians today often defend the Trinity by appealing to mystery. “It’s beyond human understanding,” they say, or “God’s nature is unlike anything else.” But when pressed, the contradictions are impossible to ignore.

The official claim is that God is one being but three persons, co-equal and co-eternal. Yet the Bible repeatedly depicts hierarchy: Jesus prays to the Father (Matthew 26:39), confesses ignorance of the end times (Mark 13:32), and declares dependence: “The Son can do nothing by himself” (John 5:19).

If the Son is truly equal to the Father, why does he lack knowledge or authority? If the Spirit is a distinct person, why is it never worshipped directly in the New Testament?

Apologists sometimes use analogies: water as ice, liquid, and vapour; or a clover with three leaves. But these analogies fall into classic heresies — modalism (God merely changing forms) or tritheism (three separate gods). Every attempt to explain the Trinity either collapses into contradiction or admits that the concept is unintelligible.

Theologian Karl Rahner famously admitted that if the doctrine of the Trinity were abandoned, most Christians would notice little practical difference in their faith. That says it all: a supposedly central doctrine is, in practice, irrelevant and incomprehensible.

Why Was It Accepted?

If the Trinity is neither biblical nor logical, why did it endure? The answer lies in power and identity.

First, it protected the divinity of Christ. By declaring Jesus to be fully God, the Church solidified his authority. No longer a prophet or messenger, Jesus became the eternal Logos, indistinguishable from God himself.

Second, it provided exclusivity. Pagan religions had many gods, but Christianity could boast a unique formula: one God in three. It sounded profound, mysterious, even superior.

Finally, it secured unity. Heresies like Arianism threatened to splinter the faith. The Trinity became a boundary marker — orthodoxy versus heresy. Accepting it was less about truth than about belonging.

Why It Doesn’t Make Sense

The Trinity is defended as a divine mystery, but in reality, it is a human invention. It emerged not from clear revelation but from centuries of argument, compromise, and political necessity.

It fails on multiple fronts:

Biblical clarity: The Scriptures never define God as three-in-one.

Logical coherence: The doctrine demands belief in a contradiction — three equals one.

Practical relevance: Most Christians live as if God were simply one being, not a triune mystery.

At best, the Trinity is theological smoke and mirrors. At worst, it’s a tool of control, forcing believers to affirm what cannot be understood, under threat of being branded heretical.

A Skeptical Conclusion

The Trinity stands as a monument to the human tendency to overcomplicate the divine. What began as simple monotheism was reshaped into a convoluted dogma to secure authority and uniformity. Christians are told to believe it, not because it makes sense, but because questioning it puts them outside the fold.

Yet if God were truly trying to reveal himself, would he do so in such an incoherent way? Why leave humanity with contradictions and councils instead of clarity? The honest answer is that the Trinity was never revealed. It was constructed.

Religion thrives on mystery, because mystery shields it from scrutiny. But once stripped of that shield, the Trinity reveals itself not as divine truth but as human invention. And if the very heart of Christian doctrine rests on an incoherent idea, what does that say about the reliability of the rest of the faith?

Perhaps it says what skeptics have long suspected: Christianity is not a revelation from heaven but a patchwork of human stories, power struggles, and theological improvisations. The Trinity is not God’s truth — it is the Church’s creation. And like all human inventions passed off as divine, it deserves not our reverence but our scrutiny and rejection.

Sources

Ayres, Lewis. Nicaea and Its Legacy: An Approach to Fourth-Century Trinitarian Theology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Kelly, J. N. D. Early Christian Doctrines. 5th ed. London: A&C Black, 1977.

McGrath, Alister E. Christian Theology: An Introduction. 6th ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2016.

Rahner, Karl. The Trinity. New York: Crossroad, 1997.

Rubinstein, Richard E. When Jesus Became God: The Struggle to Define Christianity during the Last Days of Rome. New York: Harcourt, 1999.

Young, Frances M. From Nicaea to Chalcedon: A Guide to the Literature and Its Background. 2nd ed. London: SCM Press, 2010.