When “Be Open-Minded” Means Stop Thinking

Why Christianity’s call to return thrives on vulnerability, not evidence

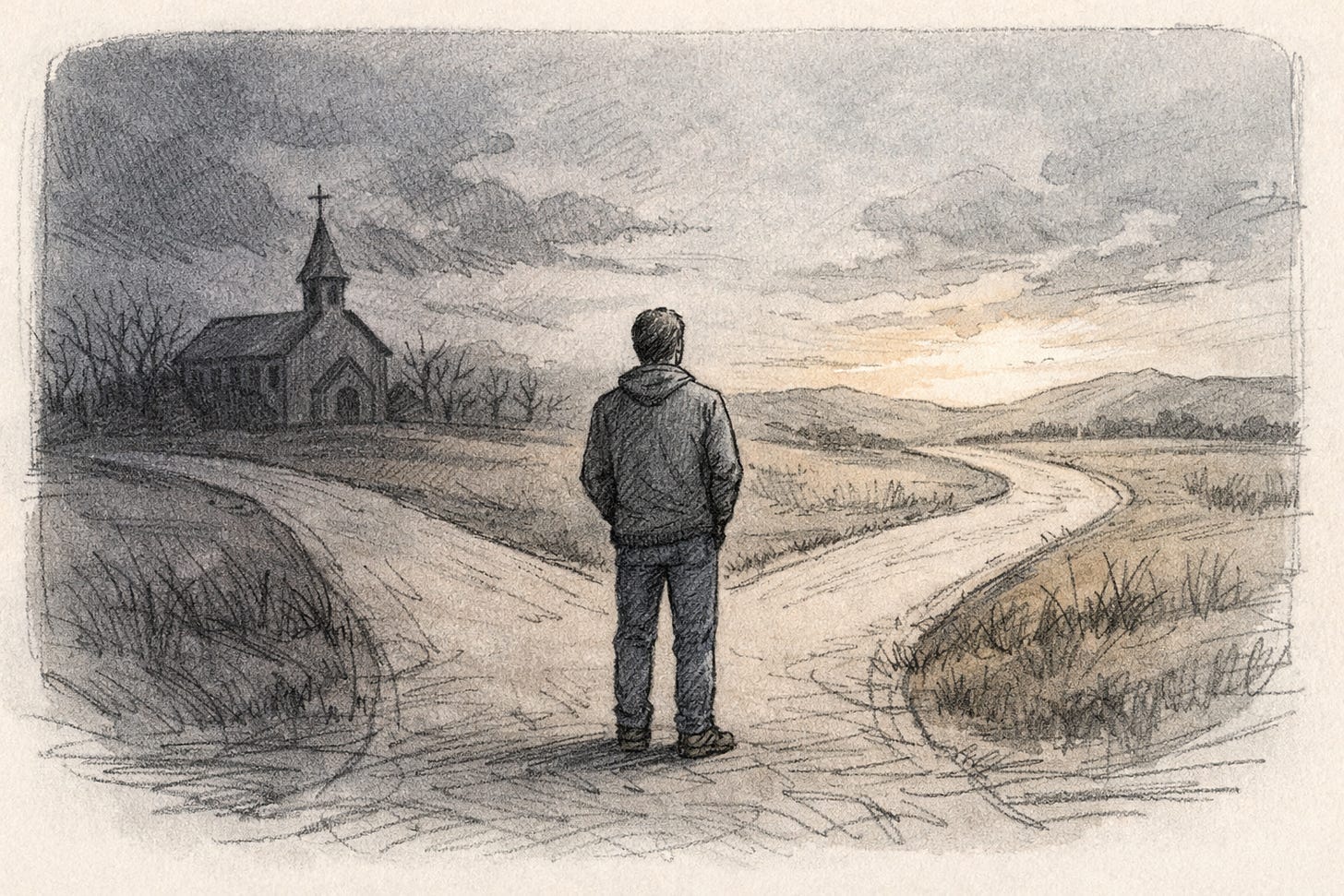

There is a moment many people experience after deconstruction that rarely gets discussed honestly. It doesn’t arrive in debate or in calm reflection. It arrives when life tightens its grip — illness, loss, failure, loneliness, fear. In those moments, old religious thoughts resurface, uninvited and unsettling. Maybe God is angry. Maybe I was wrong to leave. Maybe this suffering means something.

This return of religious thinking is often taken as evidence that belief was never really abandoned. It isn’t. It is evidence of how deeply religious frameworks embed themselves in the human psyche, especially when they were learned early and reinforced through fear, authority, and repetition. Familiar ideas return under pressure not because they are true, but because they are familiar.

The Misuse of “Open‑Mindedness”

Reality matters, because former believers are frequently told that these moments are invitations — a call to be “open‑minded” again, to give Christianity another hearing. On the surface, this sounds reasonable. After all, isn’t open‑mindedness a virtue? Shouldn’t no position be immune from reconsideration?

Yes — but only if we are honest about what open‑mindedness actually is.

Openness Versus Vulnerability

Open‑mindedness is an intellectual posture, not an emotional vulnerability. It means a willingness to follow evidence and argument wherever they lead. It does not mean reopening settled questions every time fear resurfaces. When believers urge deconstructors to be open‑minded during periods of distress, they are rarely appealing to reason. They are appealing to uncertainty, guilt, and longing — precisely the conditions under which critical thinking is most fragile.

Christianity has long relied on this dynamic. It teaches people to interpret anxiety as conviction, suffering as correction, and doubt as moral failure. Those associations do not vanish simply because belief does. They lie dormant, waiting for the next crisis. When life becomes unstable, the old explanatory system offers itself again — not as truth, but as relief.

Recognising this does not make someone closed‑minded. It makes them psychologically literate.

What Has Actually Changed?

If Christianity is to be reconsidered seriously, the first question must be brutally simple: what has actually changed? Has there been new evidence for divine claims? A clearer explanation for unanswered prayer? A moral framework that no longer depends on divine command and threat? A coherent account of suffering that does not collapse into mystery when pressed?

For most honest readers, the answer is no. The doctrines remain intact. The contradictions remain unresolved. The silence remains unexplained. What has changed is not Christianity, but the emotional state of the person reconsidering it.

The Asymmetry of Reconsideration

This is where the demand for “another chance” reveals its imbalance. Christianity is seldom required to re‑argue its claims, revise its doctrines, or accept falsification. Instead, the pressure falls on individuals to reconsider, to be charitable, to return — regardless of whether their departure involved harm, coercion, or simply reasoned disagreement. Shifting the burden this way avoids scrutiny of the system itself. That isn’t openness; it’s an asymmetrical expectation.

Thinking Clearly When It Is Hardest

Critical thinking matters most precisely when it feels hardest to maintain. Anyone can reason clearly when life is comfortable. The real test comes when fear offers certainty and familiarity masquerades as truth. In those moments, abandoning analysis may feel like humility, but it is simply surrender.

Recognising the Pull Without Surrendering to It

Acknowledging the human pull back toward belief is not a weakness. It is honesty. But mistaking that pull for insight is how control re‑enters through the side door. Reconsideration without new reasons is not courage. It is regression under pressure.

Being open‑minded does not require reopening wounds or re‑submitting to systems that failed under scrutiny. It requires clarity — especially when others insist that doubt, suffering, or fear are signs that you should stop thinking and start believing again.

If Christianity wishes to be reconsidered, it must offer more than emotional refuge. Until it can meet the same standards of evidence, coherence, and moral accountability we apply everywhere else, the most open‑minded position remains the most honest one: to recognise the pull, understand its source, and continue thinking anyway.

Sources

Berger, Peter L. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. New York: Anchor Books, 1967.

Dennett, Daniel C. Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. New York: Viking, 2006.

Draper, Paul. “God, Evil, and the Burden of Proof.” Philosophia Christi 7, no. 1 (2005): 3–30.

Festinger, Leon. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1957.

Hick, John. Evil and the God of Love. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Loftus, John W. Why I Became an Atheist: A Former Preacher Rejects Christianity. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2008.

McCutcheon, Russell T. Manufacturing Religion: The Discourse on Sui Generis Religion and the Politics of Nostalgia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Norenzayan, Ara. Big Gods: How Religion Transformed Cooperation and Conflict. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013.

Schellenberg, J. L. Divine Hiddenness and Human Reason. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993.

Stark, Rodney, and William Sims Bainbridge. A Theory of Religion. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1987.